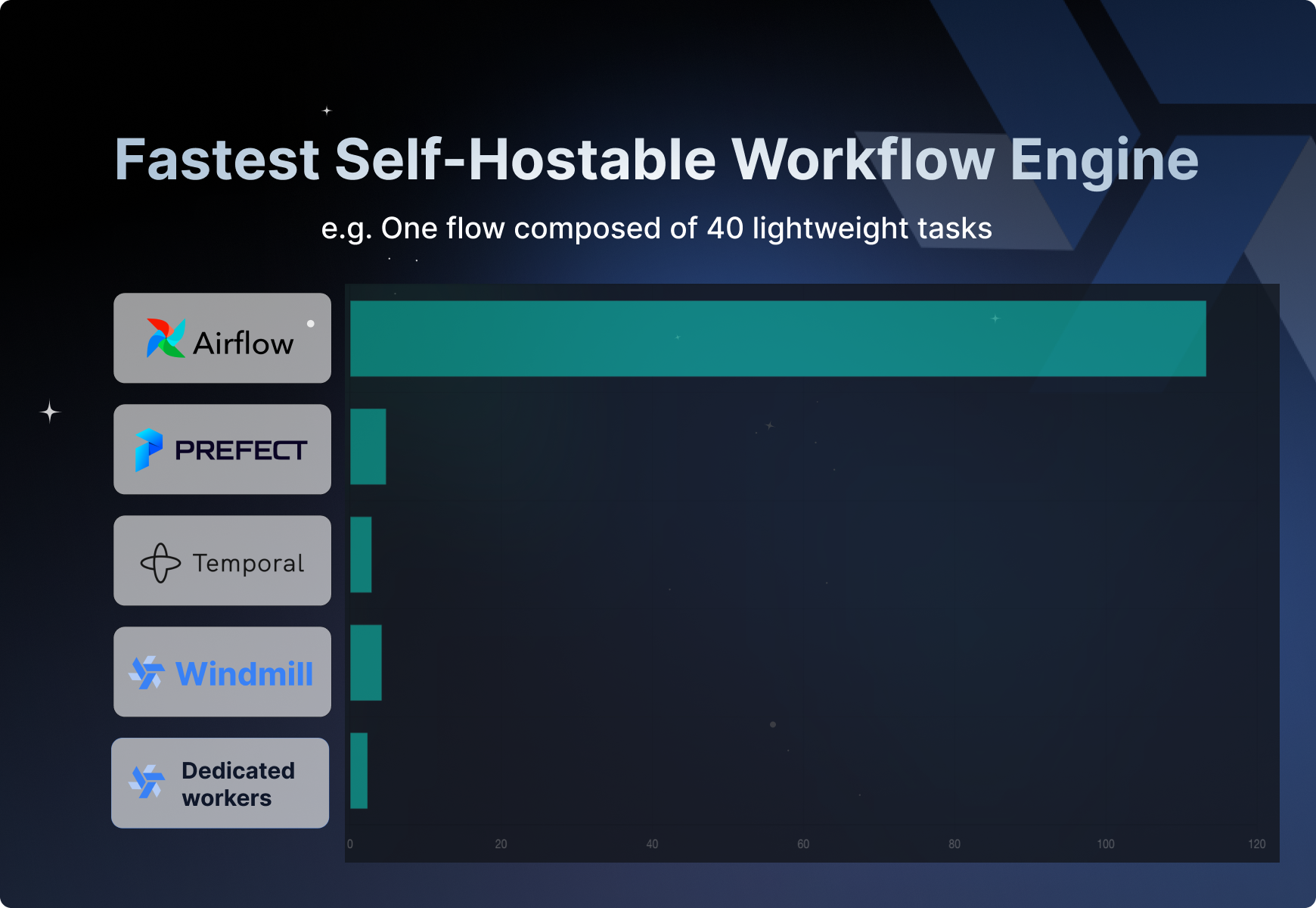

Big claim today: We've benchmarked Windmill to be the fastest self-hostable generic workflow engine among Airflow, Prefect and even Temporal. For Airflow, there is quite a margin, up to 10x faster!

Fastest self-hostable open-source workflow engine

Benchmarking data and dedicated methodology documentation.

You've known Windmill to be a productive environment to monitor, write and iterate on workflows, but we wanted to prove it's also the best system to deploy at scale in production.

It was important for us to be transparent and you can find the whole benchmark methodology here:

Enjoy the reading.

A more scoped crown

Before you raise your pitchforks, let's unpack our claim a bit, we are not claiming to be necessarily faster than your specialized, hand-built workflow engine written on top of the amazing BEAM (from which we took inspiration) but rather only among the "all-inclusive", self-hostable workflow engines. We recognize 3 main ones today:

- Airflow

- Prefect

- Temporal

There are tons of workflow engines, but not many of them are self-hostable and generic enough to support arbitrary workloads of jobs defined in code, and even those have restrictions: Some like Airflow and Prefect support only one runtime (Python). Windmill on the other hand supports TypeScript/Javascript, Python, Go, PHP, Bash and direct SQL queries to BigQuery, Snowflake, Mysql, Postgresql, MS SQL. And its design makes it easy to add more upon request. Some are notoriously hard to write for (because of complex SDKs, looking at you Airflow's XCOM or Temporal idempotency primitives) and deploy to. Windmill offers an integrated DX to build and test workflows in a few minutes interactively in a mix of raw code for the steps and low-code (or YAML) for the DAG itself. It is also possible to define them wholly with code and full version control using our VS Code extension.

One benefit of being very fast is that it makes running tests very fast too both in terms of latency to start and to run. Wasting time waiting for previews and tests to run is not fun.

Should Temporal even be there?

Temporal doesn't actually manage the workers but only the tasks queues. So even after having written your Temporal workflow, you will still need to manage your workers separately. To some degree, Temporal is not a workflow engine but a specialized durable execution engine. Windmill also supports reactivity (aka waiting for event) and can be qualified as a durable execution engine as well. That being said, Temporal is amazing at what it does and if there are overlaps between Windmill and Temporal, there are clearly use cases where you should use Temporal rather than Windmill (as the backbone of your micro-services async patterns at the scale of Uber for instance). On the other hand, sending arbitrary jobs to an internal cluster is out-of-scope for Temporal as you will still need to painfully deploy "Worker Programs" beforehand.

We leave analytics/ETL engines such as Spark or Dagster out of it for today as they are not workflow engines per se even if they are built on top of ones.

ETL and analytics workflows will be covered later this week, and you will find that Windmill offers best-in-class performance for analytics workloads leveraging S3, duckdb and polars

Workflow Engine vs Job queues

Job Queues are at the core of Workflow Engines and constitute the crux of any background job processing. There are already plenty of great queues implementations under the form of managed services (SQS), distributed scalable services (Kafka) and software (e.g: Redis with rmsq) or libraries (Orban). They are mostly sufficient to use by themselves and many developers will find satisfaction in avoiding a workflow engine altogether by building their own logic around a job queue. This is akin to writing your own specialized workflow engine.

What is a workflow engine, and what constitutes an "all-inclusive" workflow engine

First some definitions, a workflow is a directed acyclic graph DAG of nodes that represent job specifications. A workflow engine is a distributed system that takes a workflow and orchestrates it to completion on workers while respecting among others all the dependency constraints of each job. There exists a great variety of workflows and many software are domain-specific workflow engines and workflow specs (if you are a software engineer, you probably already wrote one without realizing it).

What will interest us here are workflows that can run arbitrary code in at least one major programming language (Python/TypeScript/Go/Bash). Those are the most generic but also the most complex and the most difficult to optimize. Every node is a piece of code that takes as input arguments and data from other steps (or the flow inputs), do some side effects (http requests, computation, write to disk/s3) and then returns some data for other steps to consume.

5 Major benefits of workflow engines:

- Resource allocation: Clusters can be fully leveraged and every job can be assigned to different workers with different resources (cpu, memory, gpus) and guarantee that the full resource of the worker will be available to the job

- Parallelism: When the constraints of a workflow allow some steps to be run in parallel (branches, for-loop), a workflow engine can dispatch those steps on multiple physically separate workers and not just threads

- Observability: every job has a unique ID and can be observed separately: the inputs, logs, outputs, status can be inspected

- Durability: Machine dies, side effects fail for unexpected reasons. Workflows need to be restartable as close to the unexpected events. One way of achieving this is idempotency: a single operation is the same as the effect of making several identical operations. When in doubt, replay the entire flow without any consequences. This is usually implemented with a log file and an sdk that skip the side effect when the unique id attached to an operation is part of the log. Another way is transactional snapshotting of the flow state, storing the state after each operation. To resume, simply reload that last state and execute from there. Windmill does the latter and assumes that idempotency can be implemented when desired in userland.

- Reactivity: Suspend the flow until it is resumed again based on an event such as a webhook or an approval

Additionally, an all-inclusive workflow engine should dynamically register newly available workers and make it easy to deploy new workflows, assign different jobs to different workers, and monitor the health of the workers and of the system itself.

A developer platform on top of a workflow engine should handle permissions such that different users with different levels of permissions can run different workflows and those workflows to have access to different resources depending on the roles of the caller.

So why is Windmill very fast

In a workflow engine, the term "efficiency" depends:

- efficiency to compute transitions, the new jobs to schedule given the last job that completed, and the efficiency of the workers themselves to pull scheduled jobs and run them

- efficiency to pass data between steps

- efficiency of the worker to pull jobs, start executing the code, and then submit result and new sate

Windmill is extremely fast because on all 3 aspects, it uses a simple design, optimized everywhere, that leverage maximally both Postgresql and Rust.

System design and Queue

Windmill provides a single binary (compiled from Rust) than can run both as the api server or the worker. Both workers and servers are connected to Postgresql but not to each other. The servers only expose the api and the frontend. The queue is implemented in Postgresql itself. Jobs can be triggered externally by calling the API which will push new jobs to the queue.

Jobs are stored in 2 tables in Postgresql:

- queue (while the job is not completed, even when running)

- completed_job

Jobs are not removed from the queue upon start, but their field running is set to true. Queue is implemented with the traditional UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

UPDATE queue

SET running = true

, started_at = coalesce(started_at, now())

, last_ping = now()

, suspend_until = null

WHERE id = (

SELECT id

FROM queue

WHERE running = false AND scheduled_for <= now() AND tag = ANY($1)

ORDER BY priority DESC NULLS LAST, scheduled_for, created_at

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

LIMIT 1

)

RETURNING *

This is as fast as it can get with Postgresql, as long as every field is properly indexed. Some variation of this is to delete the job from the queue instead of updating a flag, or set a time at which it is invisible for others to be pulled. It's all the same principle under the hood.

When a flow job is pushed, its inputs, pointers to an immutable flow definition and the initial flow state (see under) are pushed within the job's row (it's a big row!)

A worker will then pick the flow job, read the flow definition and flow state, realize that it needs to push the first step in the queue and that's it. This is the initial transition of the flow.

The workers pull jobs one at a time, run them to completion, and progress the state if the job is a step of a flow (that flow job is a separate job and identified with parent_job set to the flow job). The servers themselves do no orchestration, every flow transition is achieved by the workers themselves.

States

Workflow engines represent jobs as a finite state machine (FSM). The 4 main states commonly used are:

- Waiting for pre-requisites (events like a webhook to be received, or all the dependency jobs to be completed)

- Pre-requisite fulfilled, waiting for a worker to pull the job and execute it

- Running

- Completed (with Success or Failure)

Other states are usually some refinement on the 4 above

In Windmill the full flow itself is a finite state machine, where both the spec of the flow and the flow status are an easy to read struct.

A flow state is wholly defined by a step counter and an array of flow module states. Some flow module states are more complex such as the ones corresponding to for-loops and branches. One interesting aspect to note is that subflows like branches or for-loop iterations are their own well defined jobs which have a pointer to the flow that has triggered them as parent_flow.

Hence, branches and for-loops are special kinds of flow states that include an array of IDs that point to all the subflows that have been launched. When a for-loop/branch is executed sequentially, the transition consists in looking at the flow state and starting the next iteration if there is still one left, or completing that step if there isn't.

What is convenient about this design is that every state transition is just one transacted Postgresql statement. Postgresql is ACID, and we can leverage those properties to their full extent. A lot of what is hard and slow in a workflow engine is to reach eventual consistency. We skip the hard part by:

- using Postgresql which implements MVCC and row-level locks.

- do the transitions by the workers themselves at the end of their jobs

The flow state is implemented as a JSONB and hence state transitions are written in raw sql that mutate directly the flow state in the row corresponding to the flow job in the queue. It is both correct and extremely efficient. That part does not really benefit from Rust and could be implemented in any language, even in PL/SQL directly.

The 2 most tricky transitions:

- the last step of a nested flow (the branch of a branch of a branch)

- parallel branches/iterations

In details:

- At the last step of a nested flow, the worker will update the parent flow state, but will realize that that flow is now completed as well, it will simply recursively go to that flow parent and do a flow transition.

- parallel steps: Instead of running one flow at a time, all the subflows are queued when that step is launched. Then, any worker completing the last step of the subflow of each branch will increase a counter atomically. The worker that increases that counter to be as long as the number of iterations knows it needs to do a transition for the entire step since it is completed.

Additionally, processing a completed job is done in a background tokio task that receives the completed job in a channel, allowing for some degree of pipelining. Workers do not need to wait for a job to be fully acknowledged by the database to pick up another available job.

Windmill is very fast for transitions because they are implemented as raw Postgresql statements and because of pipelining between executing jobs and updating the database

Data passing

In Windmill, there are 3 main ways of doing data passing:

- every input of a step can be a javascript expression that can refer to any step outputs

Every script in typescript, python, go, bash has their main signature parsed (by a WASM program in the frontend) which allows to pre-compute the different inputs needed for a given step.

For each of those inputs, one can define either a static input or a javascript expression that can refer to the result of any step. e.g: results.d.foo where d is the id of the step.

That javascript expression when complex is evaluated by an embedded v8 using deno runtime. It takes ~8ms by expression.

Given that every step result is a job by itself that contains a result in json, it's possible to retrieve the needed result with a single sql statement. The mapping from node id to job id is kept in the flow job state.

Furthermore, most expressions are trivial and can be converted directly to raw jsonb statements:

SELECT result #> $3 as result FROM completed_job WHERE id = $1 AND workspace_id = $2"

where $3 is

json*path.map(|x| x.split(".").map(|x| x.to_string()).collect::<Vec<*>>())

- share data in a temporary folder Flows can be configured to be wholly executed on the same worker. When that is the case, a folder is shared and symlinked inside every job's ephemeral folder (jobs are started in an ephemeral folder that is removed at the end of their execution)

- pass data in S3 using the workspace object storage (updates specific to that part to be presented on day 5)

Workers efficiency

In normal mode, workers pull job one at a time, identify the language used by the job (Python, TypeScript, Go, PHP, Bash, SnowFlake, PostgreSql, MySql, MS SQL, BigQquery) and then spawn the corresponding runtime then run the job.

Workers run jobs bare, without running containers which gives us a performance boost compared to container based workflow engines. However, for sandboxing purposes, workers themselves can be run inside containers and can run each job in an nsjail sandbox.

For query languages, there is no cold start except for establishing the connection. The last connection is maintained for 1 minute to benefit from Temporal locality bash has no cold start, and go scripts are compiled AOT and then the binary is cached locally to avoid any cold starts.

Supporting executing arbitrary python code is hard because we have to support any import with any lockfiles. Since workers don't run that python code in containers, the dependencies have to be handled dynamically. To that end, we developed an efficient distributed cache system that dynamically pip install once a specific pair (package, version) and creates a dynamic virtual env on the fly to execute the code. The imports are analyzed efficiently just prior to running the code.

Similarly in typescript, the runtimes are either deno or bun so that they can benefit from global cache and never have to install the same dependency twice.

However, handling dependency fast is not sufficient for maximum speed, there is still the cold start of spawning a python (~60ms) or deno/bun (~30ms) process. In event streaming cases, the logic itself takes about 1ms and hence the cold start is 30x the overhead of running the script.

Fortunately, we implemented recently dedicated workers for scripts, which spawn a python process once at the start of the worker and then execute the script logic in a while loop, taking the job inputs in stdin and returning the output to sdout.

We extended this approach with dedicated workers for flows, which are essentially the same approach. At first, those workers will spawn a corresponding dedicated process for each of the steps implemented in Python or TypeScript. This completely obliterates the cold starts and makes Windmill flows capable of handling even-streaming use cases and going up to 1000 steps per second on each worker.

The dedicated worker for flows will pull any job relative to that flow and then route it to the proper dedicated process. Still executing only one job at a time but in pre-warmed processes.

Conclusion

Windmill is very fast because it relies on Postgresql, and Rust, and uses a simple design that enables optimizing every part, small and big. It's a bit of the same answer than why Bun is fast, which is implemented in Zig and is optimised everywhere possible.

You can self-host Windmill using a

docker compose up, or go with the cloud app.